The Words We Wield

This weekend, I went to see Croods 2 with my family. At one point, Guy (voiced by Ryan Reynolds) had an epiphany. “Words as weapons,” he uttered, finally seeing the failures that had abounded the last hour of his character’s journey. As I sit now, thinking about what I could add to TwistED Teaching’s conversation right now, that phrase sticks out in my head. “Words as weapons.” The old adage about sticks and stones aside, people have been tossing verbal grenades at each other for centuries. In some cases, the weapons are flung deliberately, after careful aim has been taken to enact maximum harm. Other times, people unintentionally stab each other with words whose deep wounds they cannot see.

Incidental Attack

As educators, we are guilty of some special varieties of using weapons as words, many carried out lacking any forethought or malice. I do not suppose the average teacher often sets out, with ill intent, to hurt a student by calling them an awful name. But how many of us are guilty of labeling students with words and phrases like troublemakers, kids like those, or rough/tough/hard students. These words are weapons just the same, striking at a student’s character instead of building it up. And even more seemingly benign, teachers often box their students into categories like dyslexic students, foster kids, or at-risk population. While it is important to know these designations, and how they affect our students, when we call them by the name of their label, we put more value on the label than we do on the child.

Though our inadvertent word-weapons pose a danger that we must learn, there are more egregious acts carried out daily in classrooms across this nation. The books we read, the curricular decisions we follow, even the way we talk about how our students talk, these fill the arsenal deployed without regard for collateral damage.

The Books we Read

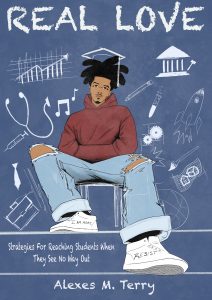

My passion, my focus, and the thing I am pursuing in my continuing education centers around diverse literature. In studying the field, inevitably you find yourself amidst the debate concerning classroom reading of books like To Kill a Mockingbird or The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. There is no simple answer, and there may not even be a “right” answer when weighing the racism in books like these against the literature that is there, ripe for analyzing and dissecting. I certainly have thoughts about reading these in class (I am against it in a whole class model), but I have heard those who generally align with my overall ideals argue for reading them. While there are certainly debatable points, I would suggest books like this bring words as weapons into the classroom. Even when discussed and treated with care, books featuring racist epithets bring focused, racist word-weapons into the class in an attack not carried out on the majority culture.

The other side of this same weapon is the reliance on books that further the cause of White Saviorism. To Kill a Mockingbird is probably the most notorious example, but there is no shortage of other titles that fit this bill. More instruments of defense than attack, narratives where White protagonists save characters of color build a shield of protection around the idea that racism only lives under hoods and in the darkest of hearts. This shield also further the generations-old mindset of an inherent superiority, as these White protagonists are often the only chance characters of color have at justice, freedom, or a better life.

Curricular Cannons

What is taught, and how it is taught, fills the quiver to more arrows. When racial slavery is dismissed as “indentured servitude” and individual slaves are called “workers,” the word-weapon equivalent of mustard gas permeates the classroom. By limiting the severity of the hundreds-of-years struggle of Africans turned African Americans, classrooms can suggest to students of any race that African (Americans) pain experienced then and expressed still is not valid – and this is one of the most dangerous word-weapons that can be deployed.

We can also weaponize a White Euro-centric or US-centric methodology in our teaching. We use semantics to romanticize history like labeling United States Imperialism “Expansion.” In so doing, education paints a picture where the United States is explicitly and always good or right, meaning other nations (including those from which many of your students may have come), must be wrong or bad. From the standpoint of patriotism, this may be acceptable. But when considering how our words are or are not being used, there is an unavoidable truth that the way we approach some subjects serves to inflict wounds to other people groups. This is why, when teaching about wars, I always pointed out that we likely consider ourselves the “good guys” in history. But so did the other side.

A Colonization of Language

Too often, we deem some language “correct,” and other language “incorrect.” As educators, we sometimes do this in a way that invalidates the language of our students. Students may be learning English because they came from another hemisphere, learning the local dialect because they moved from four states away, or learning what is culturally appropriate in a new setting because they moved from the other side of town. In any case, their words and language should not be labeled wrong, because to them, they are as natural as calling carbonated beverages ___fill_in_the_blank_with_the_word_of_your_choice___. This may not be an example of a single weapon as much as it illustrates a militarized ideology set to strip away a student’s culture so we can replace it with one we prefer.

How to Broker Peace

I would feel like I had acted irresponsibly if I pointed out the many examples of word-weapons we use without offering suggestions toward peaceful resolution. So here they are:

-Stop using labels for kids (especially around kids) like troublemaker, or rough/tough.

-Kids in care is more appropriate than foster kid, but ask if there is a compelling reason you are using even that term. In the same situation, would you be saying “kid who lives with both parents?” If not, does the child’s home status need to be mentioned in this setting?

-Take out books with language that is derogatory, at least when it uses word-weapons that take aim at specific people groups. Again, different people find different mileage with this one, but I think it bears a lot of thought before you bring a classwide book with that language. You can certainly discuss racism in literature without using a book riddled with racist epithets.

-Similarly, take out books with a White Savior theme. As with the above, your mileage may vary on this topic, but I see no compelling reason to insist on TKAM when The Hate U Give can teach just as much about justice and acting on behalf of a downtrodden “other.”

-Treat topics, in history or otherwise, with truth. There is some disagreement concerning the timing and depth of teaching students about things like slavery or the mass killing of the indigenous people in the colonies turned country. What we should not do, though, is teach falsity and half truth that serves to water down the real experience of those through the nation’s history. There is no reason that redlining or gerrymandering should be new terms to adults.

-Understand and avoid the damage that can be done through the denial of a student’s home or first language.

-When in doubt, don’t. If you are not sure if what you are using is a word-weapon, just don’t.

Zach Urquhart is a Curriculum Specialist and Instructional Coach in Midlothian, Texas. He has published articles in various local magazines and newspapers, poetry on visualverse.org and in an upcoming anthology, and is working on several manuscripts for literary journals. He is a doctoral student in the Language, Diversity, and Literacy Studies program at Texas Tech University, where he focuses on diverse literature informing privilege and Whiteness. His kids are great, and his wife is the best.

Zach Urquhart

@zurquhart